X-ray Single-Crystal Diffractometer: Methods for Eliminating Higher-Order Diffraction Interference

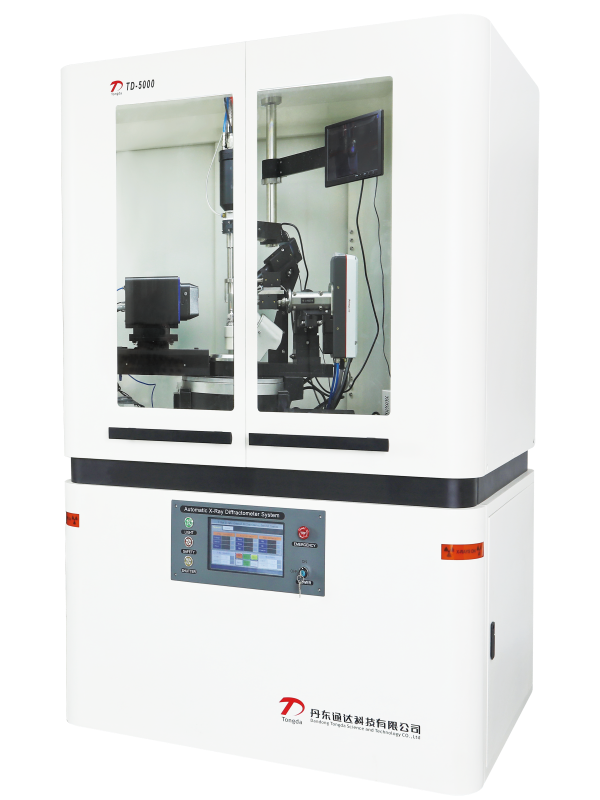

2026-01-08 11:12The X-ray single-crystal diffractometer determines core structural information of crystals—such as atomic arrangement, bond lengths, and bond angles (with precision up to 0.001 Å)—by detecting elastic scattering (diffraction) signals between X-rays and crystal atoms. It is an essential instrument in materials science, chemistry, and biology. Higher-order diffraction interference (e.g., diffraction orders with n ≥ 2, such as the 2nd-order diffraction of Cu Kα radiation) can overlap with target low-order diffraction signals, leading to peak overlap and intensity measurement errors. To ensure accurate structural analysis, a comprehensive mitigation strategy combining hardware filtration, parameter optimization, and software correction is required.

I. Hardware Filtration: Blocking Higher-Order Diffraction at the Source

Specialized optical components are used to filter X-ray wavelengths and diffraction orders, reducing the generation of higher-order signals.

Monochromatic Filtering with Monochromators: A graphite monochromator (often a curved crystal monochromator) is placed between the X-ray source and the sample. Utilizing the crystal's Bragg reflection properties for specific wavelengths, it allows only the target wavelength (e.g., Cu Kα₁ = 1.5406 Å) to pass while filtering out other wavelengths (e.g., Cu Kβ radiation, continuous radiation). These extraneous wavelengths readily produce non-target higher-order diffraction (e.g., 1st-order Kβ diffraction may overlap with 2nd-order Kα diffraction). Monochromators offer reflection efficiency ≥ 80% and wavelength purity up to 99.9%, fundamentally reducing the baseline of higher-order interference.

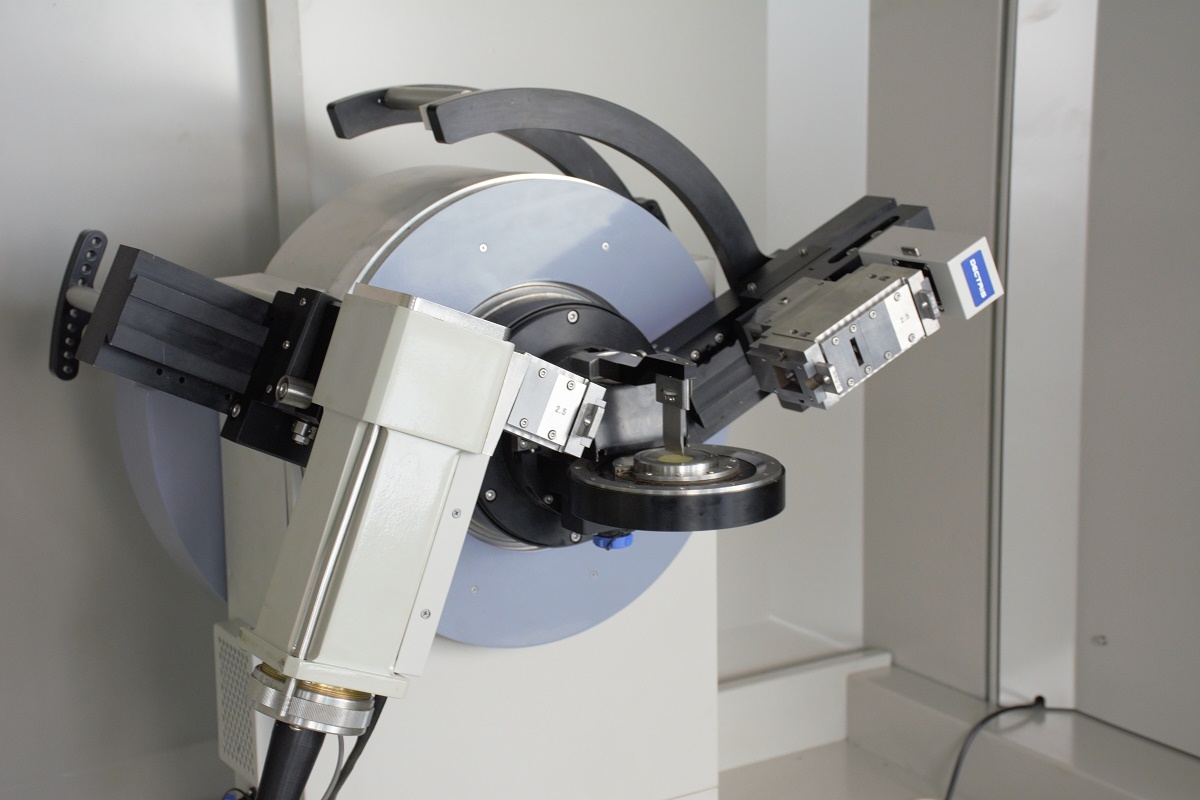

Slit and Collimator Control: A series of slits (e.g., divergence slits, anti-scatter slits) are placed between the sample and detector to control the divergence angle of the X-ray beam (typically ≤ 0.1°), minimizing stray signals from non-Bragg diffraction. Combined with collimators (e.g., capillary collimators) that produce a parallel beam incident on the sample, this prevents the spread of higher-order diffraction signals due to beam divergence, ensuring the detector receives signals only from the intended diffraction direction.

II. Parameter Optimization: Suppressing the Detection of Higher-Order Diffraction Signals

Experimental parameters are adjusted to lower the probability of erroneously detecting higher-order diffraction.

Control of Diffraction Angle Range and Step Size: The Bragg angle (2θ) is calculated based on the target crystal's lattice parameters. Scanning is performed only within the 2θ range of the target low-order diffraction (e.g., for small-molecule crystals using Cu Kα radiation, 2θ is typically set between 5° and 70°, avoiding high 2θ regions prone to higher-order diffraction). Simultaneously, reducing the scan step size (e.g., 0.01°/step) enhances diffraction peak resolution, allowing clear separation between low-order and potential higher-order diffraction peaks and avoiding intensity misjudgment due to overlap.

Detector Energy Resolution Function: Employing detectors with energy resolution capability (e.g., CCD detectors, pixel array detectors) leverages the energy difference between different diffraction orders (higher-order diffraction energy = n × low-order energy, where n is the order). By setting an energy threshold during detection (e.g., accepting only signals matching the low-order energy), high-energy signals from higher-order diffraction are automatically rejected. Energy resolution precision can reach 5 eV, with a higher-order signal rejection rate ≥ 95%.

III. Software Correction: Eliminating Residual Higher-Order Diffraction Effects

Data processing algorithms are used to correct for minor residual higher-order diffraction interference.

Diffraction Peak Profile Fitting and Separation: The acquired diffraction pattern is subjected to peak profile fitting (commonly using the pseudo-Voigt function). If overlap exists between low-order and higher-order diffraction peaks (manifested as asymmetric peak shapes or shoulders), the intensities and positions of the two peaks are separated via fitting to extract pure low-order diffraction intensity data. Concurrently, the reasonableness of the fitting results is verified using the crystal's structure factor calculations (based on theoretical models), ensuring effective stripping of higher-order interference.

Higher-Order Correction During Structure Refinement: In the crystal structure refinement stage (e.g., using SHELXL software), a "higher-order diffraction correction factor" is introduced. Based on the X-ray wavelength and lattice parameters, the theoretical intensity of higher-order diffraction is calculated and compared with experimental data to correct the intensity of affected low-order diffraction. The effectiveness of correction is monitored via residual factors (R1, wR2). Typically, post-correction R1 ≤ 0.05 indicates that higher-order interference has been reduced to an acceptable level.

Additionally, sample preparation requires supportive measures: select single-crystal samples of appropriate size (e.g., 0.1–0.5 mm) to avoid multiple diffraction caused by overly large samples (which can easily generate higher-order interference). If the sample exhibits orientational disorder, low-temperature cooling (e.g., -173 °C) can be used to fix crystal orientation, reducing fluctuations in higher-order diffraction signals due to orientation changes.

Through the above methods, the X-ray single-crystal diffractometer can control intensity errors caused by higher-order diffraction interference to ≤ 2%, ensuring high precision in crystal structure determination.